Elizabeth Stern’s cancer research has had a lasting impact on women’s health

Blog Post

Cancer treatment was undergoing a revolution in the mid-20th century. In 1928, Dr. George Papanicolaou developed a cellular screening test for uterine and cervical cancer, and with this discovery he essentially founded the modern field of cytopathology. Today this test is referred to as a Pap smear, and was adopted in the 1960s as a standard screening tool for cervical cancer in the United States. Cervical cancer rates have fallen nearly 70% from the 1950s, credited mainly to the development of the Pap test.

Cytopathology refers to the diagnosis of disease at the cellular level, and the Pap test provided an easy method to gain tissue samples for analysis and comparison. The availability of such clinical samples spearheaded a major research effort to define the stages of cervical cancer progression. Earlier detection of cancer leads to less invasive treatment and decreased morality. In the 1960s, however, doctors were still unsure how to properly diagnose the initial stages of cervical cancer based on these cytopathology reports.

This is where Elizabeth Stern’s story begins.

Cervical cancer research

Elizabeth Stern was born on Sept. 19, 1915, in Cobalt, Ontario. She earned her medical degree at the University of Toronto in 1939 and moved to the United States in 1940, where she advanced her medical training in pathology at University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and at the Good Samaritan and Cedars of Lebanon hospitals in Los Angeles. She accepted a teaching position at the UCLA School of Public Health in 1963 and was promoted to full Professor of Epidemiology in 1965, after which she began her groundbreaking work in the fields of cytopathology and cervical cancer.

In the early- and mid- 1960s, Stern published a number of studies analyzing the risk of cervical dysplasia to the development of cervical cancer. Dysplasia refers to abnormal cell growth that is non-invasive to surrounding tissues, and in Stern’s studies, she wanted to determine if dysplasia in the cervix correlated with increased development of cervical cancer. It was completely unknown at the time if these dysplastic cells should be treated as cancerous, or if they were just small aberrations that would clear up on their own over time. Stern’s aim was to define how cervical cells change during cancer progression, and if dysplasia was a step in this process from normal cell to malignant tumor.

Her largest study was published in 1963 in Acta Cytologica, and analyzed the consequences of cervical cell dysplasia in over 10,500 women in the Los Angeles County area over a 2-year period.

At the time of their first test she noted that the majority of women had normal cervical cell morphology, and only 94 women demonstrated cervical cell dysplasia. Two years later women returned for a second Pap test, and Stern observed 13 new cases of cervical cancer. 11 of these cases were diagnosed in the relatively small group of patients with dysplasia. To put it more simply, 85% of the cancers occurred in less than 1% of the subjects.Although these results are not irrefutable proof, the size and scope of this study clearly demonstrate that dysplasia is correlated with increased cervical cancer risk. And overall, this indicates that dysplastic cell morphology is linked to cancer development.

Stern followed patients from this initial study, confirming that patients with dysplasia are more likely to develop cervical cancer over time. She found that even when cervical cell dysplasia resolves, the dysplasia is more likely to return and progress to cancer in these same patients. Stern’s research defined dysplasia as one of the earliest hallmarks of cervical cancer, with the ability to progress as well as regress back to normal morphology.

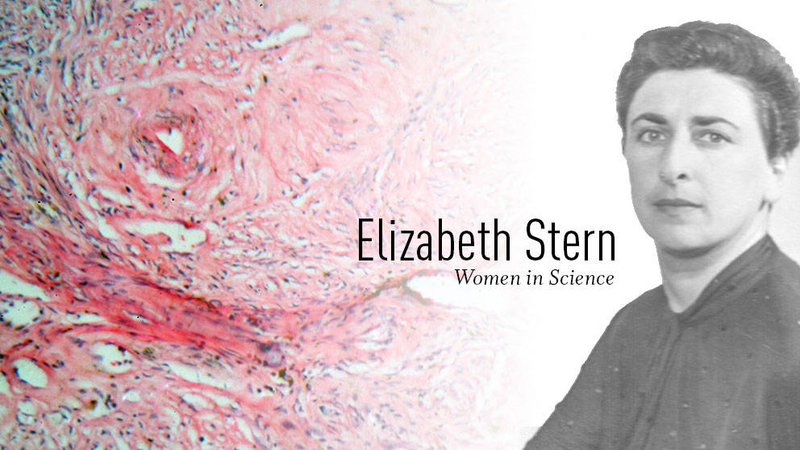

She built on this wealth of data and began to analyze cervical cells from patients at different stages of cancer development. In 1974, Stern and her colleagues at UCLA published in Cancer Research, in which they outlined and provided histological examples for each stage of cervical cancer. Her 100-point scale ranked the progression of cervical cancer, including multiple stages of atypical cell morphology and dysplasia, and was very finely detailed, allowing for doctors to qualitatively assess cervical cancer development.

The pill and cervical cancer risk

In 1960, the FDA approved the combined oral contraceptive pill Enovid, colloquially known as “the pill,” for contraceptive use. The pill’s popularity skyrocketed, and by 1965 at least 6.5 million married women in the United States were using the pill.

Few studies had been performed to assess the long-term consequences of taking birth control pills. It is crucial to note that these early forms of birth control pills were drastically different from the ones on the market today. Enovid contained roughly 10 times the amount of estrogen compared to today’s low-dose oral contraceptives. This is a substantial difference! These high-dose birth control pills caused a range of adverse side effects including blood clots, depression, heart attack, and stroke, and in the late 1960s newspapers began to report on the dangers of the pill.

In the same time-frame, Stern began studying possible links between birth control pill use and cervical cancer, carefully selecting her patients from the more than 10,000 women that visited the LA County family planning clinics. She chose women with and without dysplasia that were interested in starting oral contraceptives, along with control patients that did not take the pill, and analyzed cervical cell morphology over the course of 7 years. Her results were published inScience in 1977, and the data were striking: by the conclusion of the 7-year study, women on the Pill had a 6-fold increased risk for cervical cancer compared to nonusers.

Her publication in 1977 linking birth control pills to increased cervical cancer rates provided further scientific corroboration that these pills were not safe for women. By 1979 birth control pill sales were decreased 24% compared to their height of popularity in the mid-1960s. Ultimately these high-dose estrogen pills were pulled from the market in favor of lower-dose hormone pills, which have fewer side effects and more benefits, including lowered risk of ovarian cancer and pelvic inflammatory disease.

Women’s health care

As her publications illustrate, Stern worked a great deal in the Los Angeles County family planning clinics. She also had a vested interest in providing healthcare to disadvantaged populations in Los Angeles. Stern published a study in 1977 demonstrating that the highest rates of cervical cancer in Los Angeles occurred in the regions with the lowest median income, and were predominately black and Hispanic. Stern wanted to figure out how to reach these women and provide much-needed medical care.

She piloted a small study that opened short-term clinics in communities identified in her previous research, and recorded observations on multiple aspects of this experience. This study provided transportation and free baby-sitting to encourage participation, and they trained health workers from the community to interact with and recruit patients to attend the free clinics.

In 1979 she published her results, which showcase women’s need for flexibility in accessing healthcare, particularly in the hours of operation and in the location of the clinic in their neighborhoods. I found the paper incredibly insightful. For example, in their clinics, they explained the procedures thoroughly to their patients, and ensured that only female nurses or doctors performed the Pap test. This detail is important, as she found that 77% of participants preferred a female to conduct the test, and that many women initially cautious agreed to attend the clinic upon learning that a woman would perform their exam.

This paper concludes with the call for permanent clinics to be established in these neighborhoods, to facilitate regular gynecological health care and educate women on the importance of these screening tests. Stern would have undoubtedly continued this work, but in 1980 she passed away from stomach cancer. Today, Los Angeles County Department of Health has a division fully committed to providing free or low-cost women’s health care, with 17 different locations across Los Angeles County.

A lasting legacy

Elizabeth Stern’s research influenced women’s health in multiple fields. She defined the progression of cervical cancer from dysplasia to invasive cancer, and provided clinical evidence for dysplasia as an early hallmark of cervical cancer. Because of her findings, doctors perform routine Pap smear tests and can identify cervical cancer at earlier stages. She was also determined that these health care improvements would be available to everyone. Although she is not a household name, Stern’s work has had a lasting impact on women’s healthcare, improving cervical cancer diagnosis and promoting the inclusion and protection of all women against disease.

Ellen Elliott, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral fellow at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine in Farmington, Conn. Ellen works in the laboratory of Adam Williams, Ph.D., where she is studying the function of long non-coding RNAs in TH2 cells and asthma. Follow Ellen on Twitter at @EllenNichole.