Battling SPG50 and changing the world

Featured Article | August 18, 2022

Georgia Pirovolakis will never forget the moment her sneaking parental suspicion about her son became reality. Getting Michael’s diagnosis was essential, and it all started when she, “Felt that something wasn’t right!” as her husband, Terry, put it.

A sick feeling turned grim reality

The new parents first suspected something was amiss with Michael, born December 17th, 2017, when he wasn’t lifting his head or hands by five months-old. As the weeks rolled on, they tried to determine the cause of these missed milestones, and if it was connected to Michael’s low muscle tone and his smaller- than-average head. Within his first year, muscle tone and mobility improved, but doctors found a thinning of the corpus callosum and abnormal white matter on an MRI of his brain. Soon after this discovery, Michael had a major seizure, which wiped out a lot of the physical progress he had made.

Finally, in April of 2019, the family had Michael’s genome analyzed, and doctors found a gene mutation that causes the rare disease SPG50 (AP4M1).

“The diagnosis was devastating,” says Terry Pirovolakis, “we knew something was wrong, but knowing exactly how terrible the disease was devastating, a piece of our souls was taken when we found out.

SPG50, or Spastic Paraplegia Type 50, is known to affect only around 80 people worldwide. It is a rare disease that typically starts with low muscle tone, microcephaly (small head) and epilepsy, then goes on to affect the whole body. The disease typically sets in at the toes and works its way up, with most patients experiencing lower body paralysis from spasticity by age 10 and becoming quadriplegic later in their lives. The disease also comes with mental disabilities, with many never being able to walk or talk. Its effect on lifespan isn’t known as the disease was only recently cataloged, and there are few known adults with the condition.

The rare disease odyssey begins

After the diagnosis, the Pirovolakis family leapt into action. They spoke with families with a similar rare disease (SGP47, SPG15, CMT4J, etc..), read articles, and attended conferences. Within a month, Pirovolakis attended an American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy conference, hoping to gather information and meet experts who could help.

“I went in cold,” Pirovolakis explains, “I didn’t know anybody there, so I put up ‘Wanted’ posters with my son's face on them and my information, asking for anyone with any information about SPG50 to contact me. I setup coffee meetings with the FDA, NIH, Gene Therapy companies, and world experts in the field, anyone that would speak with me.

All this eventually led to a meeting with Dr. Steven Gray, a leading molecular biologist who gave Pirovolakis mixed news. The good news was that it was possible to “repair” the mutated gene and the damage of SPG50 could theoretically be reversed. The bad news, which affects so many rare disease families, is that this treatment hadn’t yet been created. To make matters worse, testing such a treatment (with no guarantee of success) would run at least $3 million.

Undaunted, Pirovolakis and his family decided to take the expensive gamble: “We almost immediately cashed out our life savings and started reaching out to research groups. The money wasn’t nearly enough, but we knew we had to get started as soon as possible. It was scary signing contracts worth more than my home before even raising a single penny.”

Among the first steps was finding a mouse. This was crucial, as it would be the only way to safely test out potential treatments. Pirovolakis says everyone referred them to The Jackson Laboratory (JAX), due to their mouse and rare disease expertise. Pirovolakis was impressed with how fast JAX turned around and helped.

“I left a message with the lab, crying, and I was amazed at how fast JAX stepped up. JAX had a mouse ready to go almost immediately and had one shipped in from the UK as well.” Pirovolakis says. “The mouse is absolutely foundational in treating rare disease, and JAX didn’t make us wait. JAX has a lot of humanity; they let us know as soon as the mice were ready.”

Cathleen “Cat” Lutz, Ph.D., M.B.A., vice president of the Rare Disease Translational Center at JAX, started the journey with Pirovolakis and is still working with him in navigating the treatment process today. “At JAX we make sure we have the mouse resources and models for people ready to go; we often need to genetically engineer the mice to contain the exact mutations they’re working with,” says Lutz. “It’s so inspirational to me, on a personal level, to see parents going through these lengths for their children, but at the same time it’s terrible that it all falls on their shoulders to create a treatment from scratch.”

Working with Lutz and the newly developed mouse model, Pirovolakis dove into the exhausting work of exploring potential cures for SPG50, reaching out to Boston Children’s and the National Institute of Health (NIH), among others. Sorting through research and leaning on the expertise of Dr. Gray and others, Pirovolakis soon had gathered enough evidence that pointed to a potential treatment.

A multinational effort to cure SPG50

As the research continued, so did the Pirovolakis’ need to raise funds. “We wanted to buy in as early as possible so we wouldn’t have to wait for the money to continue the research and treatment process,” said Pirovolakis. “The crazy thing is, the community helped us so much we basically just got to show up at events! Our community here [in Toronto] is amazing and really rallied around us.”

While discussing approaches to treatment with Lutz at JAX, the Pirovolakis family had to raise money for Michael’s eventual treatment (covering the development & manufacturing of the genetic treatment, administering the treatment itself, and many other medical necessities). Events were planned all over Canada and around the world. Everything from collection boxes in community centers and churches, to soccer and golf tournaments, bicycle rides, marathons, and more helped chip away at the enormous cost of developing a therapy using JAX’s mice. But eventually the colossal sum of $3 million was raised. Though this is a staggering number for one person to raise, it is unfortunately common for rare disease families to shoulder this burden themselves.

A collage of some of the fundraisers crated to raise money to find a cure for Michael and SPG50.

A collage of some of the fundraisers crated to raise money to find a cure for Michael and SPG50.

“We are happy to direct and guide families, and we try to have grants and programs ready for rare disease families,” Lutz says, “But sadly we don’t have funding to do everything, so that means families have to seek out programs on their own. End of the day, it takes a village to cure a rare disease, and it would be so much better if individual families didn’t have to go through all the fundraising and research and treatment connections by themselves.”

As the Pirovolakis continued their quest, they hit a snag that threatened all of their progress: COVID-19. But they were up for the challenge, and, leaned on socially distant activities like long-distance bicycle riding to continue building the groundwork for a potential eventual treatment.

Attacking a rare disease on a genetic level

By 2020, working with a multinational group of medical experts and researchers, the big question remained of whether a treatment should be manufactured. The testing results showed that the treatmentcould work, although success was far from certain. Some issues lingered, but eventually the Pirovolakis family took the multimillion-dollar gamble. “The final efficacy wasn’t super strong, due to the slow nature of the disease,” Pirovolakis says, “but it was enough to show it could work and get the treatment to the clinic.”

Pirovolakis continually focuses on how much medical experts and facilities have helped his family. All through 2020, at the height of COVID-19, researchers would still volunteer to mask up and work on the treatment in the lab. They met regularly with Lutz at JAX to maintain a focused development plan of the treatment. Medical facilities even went as far as donating their time and materials. “The cost for all of this was around $7-10 million.” Pirovolakis said, “If we didn’t get the donated help and material from medical facilities, the cost would have been well over $25 million.”

A roadmap of the steps needed to go through to create a SPG50 treatment.

A roadmap of the steps needed to go through to create a SPG50 treatment.

All of the effort helped lead to the big day, December 30th, 2021, when Health Canada formally approved the clinical treatment that would, hopefully, save the life of Michael and all those affected by SPG50.

With the final hurdle of research and development cleared, Michael went into treatment at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) affiliated with the University of Toronto on March 24th. The impacts of the treatment are still being examined, but the Pirovolakis family is hopeful.

One battle ends, but the war on rare disease remains

Pirovolakis has been so changed by this ordeal that treating Michael—or even every child with SPG50–isn't enough; rather they want to change the way rare disease is approached on an institutional level.

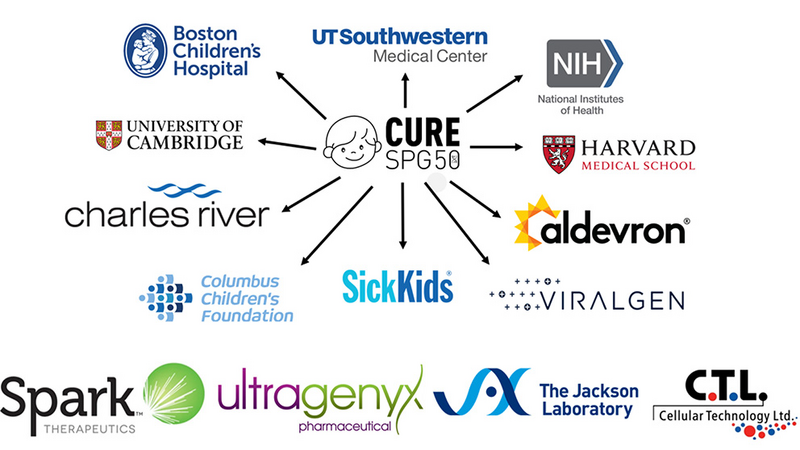

It took over a dozen research institutions and laboratories working all over the globe to develop the treatment for Michael. JAX started with the mouse, but Pirovolakis then reached out to institutions including Charles River Laboratories, The University of Cambridge, the NIH, Harvard Medical School, SickKids, and many more to figure out how the mouse could be used to develop treatment. Pirovolakis knows there is a better way.

Going the extra mile, Pirovolakis has started reaching out to government officials around the world, urging them to look at other global models of rare disease treatment. “There are models in places like France and the Netherlands,” says Pirovolakis, “Where rare diseases are cataloged and knocked out with government funding one by one. If that doesn’t seem like a lot at a time, imagine if the US government decided to cure a handful a year. We have the technology and know-how to make sure we never see these diseases again, we just need the funding.”

In particular, Pirovolakis has been focused on the U.S. and Canada. It’s important to start here, he stresses, as if the U.S. decided to adopt something like this, then the rest of the world will follow.

Some of the groups that the Pirovolakis worked with to develop a treatment for SPG50

Some of the groups that the Pirovolakis worked with to develop a treatment for SPG50

Pirovolakis has no doubt that something will eventually change, but he is urging everyone to act fast. “Thousands of children die every day from a rare disease. It’s a significant number. Rare diseases, on the whole, aren’t rare at all. This isn’t an issue for families to attack one by one on their own,” Pirovolakis says, “it’s a humanity issue. It shouldn’t be this hard for families to save their kids with technology that currently exists and is fully realized.”

As for his message to world leaders, Pirovolakis shares a sobering, but encouraging, statement: “Be the hero’s we need you to be now because our children deserve to live better lives. We are lettingour children down every day we stand by and do nothing! We can save these children we just need you to step up and help us….,” he says. “Everything is in place for us, as a world, to start knocking out rare diseases, we just need governments to do it.”

The Pirovolakis family is working on getting the SPG50 gene therapy to the US and the rest of the world as fast as possible to ensure other kids can be saved as well. For more information on CureSPG50,visit their website. All graphics in this article are courtesy of Terry Pirovolakis.